In a groundbreaking study, researchers have uncovered that the North China settlement of Jiahu not only survived the abrupt climate event known as the 8.2 ka event but also exhibited significant social transformations during this challenging period. Rather than facing destruction, Jiahu demonstrated remarkable resilience, challenging the narrative that this climatic event was universally catastrophic across the region.

The 8.2 ka event, identified in Greenland ice core samples, caused significant cooling and drying across the Northern Hemisphere. Triggered by the collapse of the Laurentide ice sheet in North America, this event disrupted climate systems and forced a southward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, severely impacting agricultural regions reliant on the East Asian Summer Monsoon. Despite the turmoil affecting surrounding settlements, which often faced abandonment, Jiahu adapted and thrived.

Resilience Theory Applied to Ancient Societies

To explore how Jiahu managed to withstand this climate crisis, Dr. Yuchen Tan and their team utilized resilience theory in combination with the Baseline Resilience Indicator for Communities (BRIC) model. Originally developed for ecological studies, resilience theory examines how systems absorb disturbances and reorganize in response. The BRIC model assesses how modern communities handle natural disasters, focusing on social, economic, institutional, and infrastructural factors.

Dr. Tan explained, “Our aim in adapting BRIC was to provide a transferable framework for examining how human systems reorganize in response to abrupt climatic or environmental change across a wider range of sites.” By applying these modern principles to archaeological contexts, the researchers aimed to derive more structured insights into the resilience of ancient communities.

Social Transformations at Jiahu

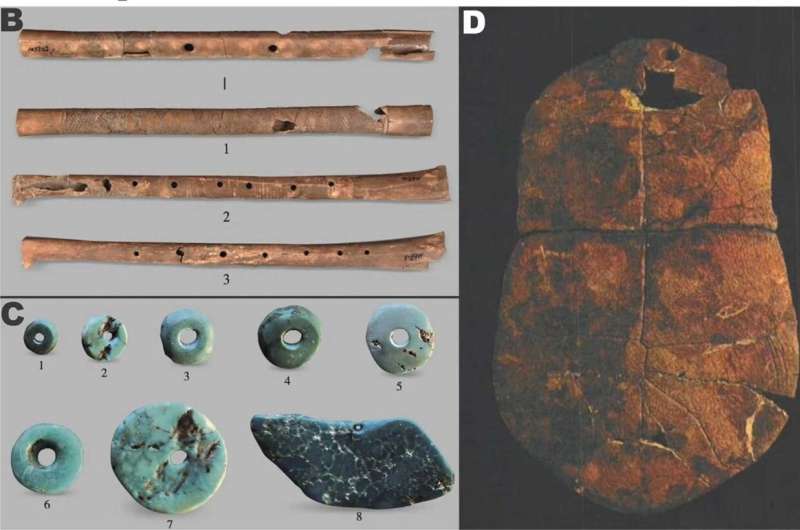

The researchers analyzed archaeological evidence from the three distinct occupation phases of Jiahu: Phase I (9.0–8.5 ka BP), Phase II (8.5–8.0 ka BP), and Phase III (8.0–7.5 ka BP). Notably, Phase II coincided directly with the 8.2 ka event and revealed dramatic social transformations. The number of burials surged from 88 in Phase I to 206 in Phase II, likely reflecting both increased mortality and an influx of immigrants from surrounding areas.

This period also saw more standardized burial practices and an increase in grave goods, suggesting growing wealth disparities and social stratification. Analysis of skeletal remains indicated a greater division of labor, particularly among males, who exhibited higher rates of osteoarthritis, potentially due to their involvement in more physically demanding tasks.

The influx of migrants and the enhanced division of labor likely strengthened Jiahu’s workforce, enabling the community to effectively secure food and navigate the challenges posed by the climate event.

By Phase III, however, burial numbers decreased to 182, and grave goods became rarer. Dr. Tan noted that the ultimate collapse of the Jiahu settlement did not occur until after Phase III, when ongoing climatic fluctuations led to severe flooding, rendering the previously functional habitats uninhabitable.

The findings from Jiahu provide valuable insights into how ancient communities could adapt to significant environmental changes. The successful application of the BRIC model in this archaeological context highlights the potential for future studies to explore resilience in other historical societies.

Ultimately, this research underscores the complexities of human adaptation, suggesting that the impacts of the 8.2 ka event were not uniform and that some communities, like Jiahu, were capable of remarkable resilience and transformation in the face of adversity.