A recent study reveals that a specific genetic variant may reduce the risk of certain blood cancers by 20%. Conducted by a team led by Vijay Sankaran, a physician-scientist at Boston Children’s Hospital and the Broad Institute, the research focuses on a phenomenon known as clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP). This condition involves the accumulation of mutations in hematopoietic stem cells, which can lead to aggressive cell division and, potentially, blood cancers like leukemia.

The findings, published in the journal Science on March 7, 2024, suggest that individuals possessing a variation that lowers levels of the protein Musashi2 (MSI2) are significantly less likely to develop myeloid malignancies. This genetic variant appears to have a protective effect, as those with it are 1.8 times more likely to see a reduction in the expansion of CHIP clones.

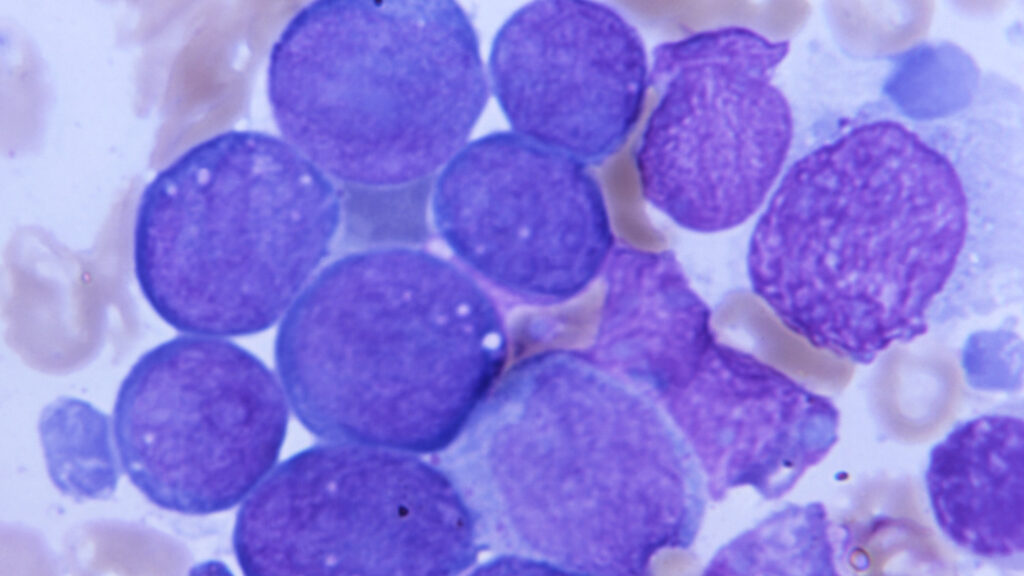

Hematopoietic stem cells are essential for producing blood cells, including red blood cells and platelets. As these cells replicate, they may acquire mutations that contribute to CHIP. While not all individuals with CHIP will develop cancer, the condition is associated with a heightened risk, increasing the likelihood of blood cancers by three to five times compared to the general population.

Sankaran’s team analyzed data from large biological databases, including the UK Biobank and the All Of Us Study. They discovered that the genetic variant linked to reduced MSI2 levels correlates with a decreased risk of myeloid cancers. The aberrant growth of mutant stem cells can lead to a larger population of clones; however, the presence of this variant may act as a brake on this overactivity.

The implications of these findings are significant. “Identifying a protective variant like this is groundbreaking,” noted Koichi Takahashi, an oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, who was not involved in the research. He emphasized that understanding how the MSI2 protein influences cancer development could pave the way for innovative treatments.

While the potential for developing preventive therapies is promising, challenges remain. Currently, there are no established methods to downregulate MSI2 levels effectively. Although the study highlights a link between the protective variant and a reduced risk of blood cancer, individuals with this genetic trait also exhibited lower overall blood counts. This raises concerns about possible side effects, such as increased risks of bleeding or infections.

Despite these concerns, some individuals with CHIP face a significantly higher risk of blood cancers, particularly those with high-risk mutations like TP53. In high-risk cases, the probability of developing blood cancer within the next 5 to 10 years can soar to 60%. “If treatment can reduce or eliminate the risk of developing myeloid malignancy, a mild level of toxicity from any potential therapeutic may be acceptable,” Takahashi remarked.

Sankaran hopes that this research will catalyze further investigations into MSI2 and its role in cancer risk. “The field has advanced significantly in identifying CHIP and understanding its associated risks,” he stated. However, the challenge remains in determining effective interventions once CHIP is diagnosed. The insights from this study could ultimately lead to viable therapeutic options for high-risk patients experiencing a condition that has long lacked effective treatment strategies.