Research from New York University has unveiled thousands of preserved metabolic molecules within fossilized bones, providing unprecedented insights into ancient life. These findings reveal critical information about the diets, diseases, and climates of animals that roamed the Earth between 1.3 and 3 million years ago. The research indicates that the environments were notably warmer and wetter than those in the same regions today.

For the first time, scientists successfully examined metabolism-related molecules in fossilized bones. This approach sheds light on ancient ecosystems, allowing researchers to gather detailed information about the health and diets of prehistoric animals and the climates they inhabited. The results were published in the journal Nature.

Uncovering Prehistoric Metabolism

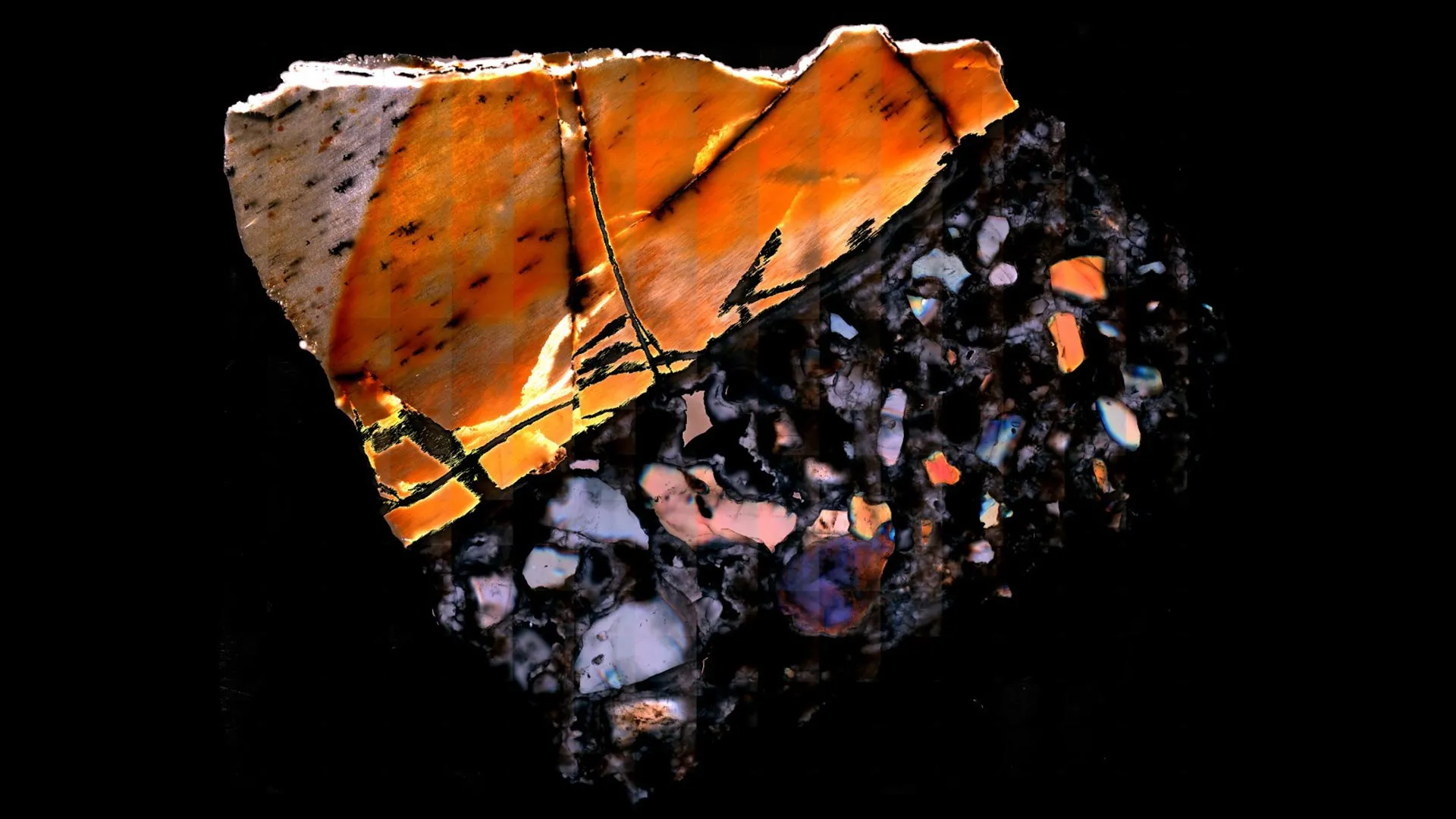

The research team, led by Timothy Bromage, a professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU, utilized mass spectrometry to analyze the preserved bones. This technique can identify and quantify metabolites—molecules produced during digestion and other bodily processes. While metabolomics has been a significant tool in modern medical research, its application to fossils is relatively new. Most studies have relied heavily on DNA analysis, primarily to establish genetic relationships.

Bromage’s interest in applying metabolomics to fossils stemmed from earlier discoveries that collagen, a protein found in bones, can survive millions of years. He proposed that metabolites might also be preserved within the bone’s microenvironment. This hypothesis was confirmed when tests on modern mouse bones identified nearly 2,200 metabolites.

Insights from Fossils

The team examined animal bones from sites in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa, known for their early human activity. The fossils included remains from various species, such as rodents and larger animals like antelopes and elephants. Thousands of metabolites were identified, many matching those found in living relatives.

The metabolic analysis revealed numerous biological processes, including amino acid breakdown and essential nutrient absorption. Some metabolites indicated the gender of specific fossils, while others pointed to health issues. Notably, a ground squirrel bone from Olduvai Gorge showed signs of infection by the parasite Trypanosoma brucei, the causative agent of sleeping sickness. This discovery illustrated the squirrel’s immune response to the parasite’s presence.

In addition to health insights, the research provided clues about the diets of these ancient animals. Although databases of plant metabolites are less comprehensive, the team identified compounds linked to local flora, such as aloe and asparagus. This information allows scientists to reconstruct the environmental conditions in which these animals lived, including temperature, rainfall, and soil conditions.

The findings align with previous geological research, which described the Olduvai Gorge as a freshwater woodland and grassland habitat. Overall, the fossil evidence consistently points to climates that were more humid and warmer than the current conditions in these regions.

Bromage emphasized the transformative potential of using metabolic analyses to study fossils: “We can build a story around each of the animals,” he stated. This innovative approach enables researchers to reconstruct ancient ecosystems with a level of detail comparable to contemporary field ecologists.

The research team included Bin Hu, Sher Poudel, Sasan Rabieh, and Shoshana Yakar from NYU, along with collaborators from institutions in France, Germany, Canada, and the United States. The study received funding from the Leakey Foundation, with additional support for equipment from the National Institutes of Health.

Through this groundbreaking research, scientists are opening new avenues for understanding ancient life and the environments in which it thrived.