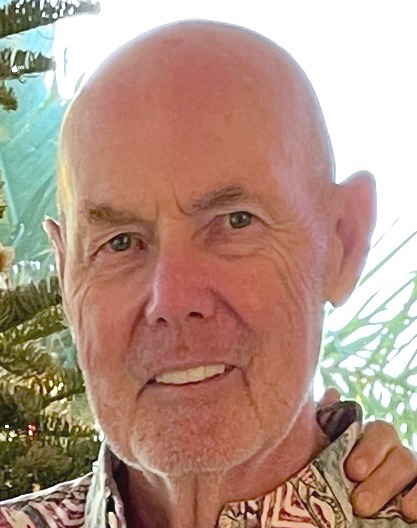

On January 1, 2022, Colin McGarva jumped into a flooding river in Worcester to rescue an unconscious woman. McGarva acted instinctively, disregarding the potential risks to himself, including the heart-wrenching possibility of leaving behind his newborn son. “I didn’t stop to think because the instinct – the instant reaction – is to help someone in need,” he stated. This incident highlights a growing conversation about the nature of heroism and bystander behavior in emergencies.

The topic gained further attention following a mass stabbing attack on a high-speed train from Doncaster to London. Initial reports described chaos as passengers fled the scene, but stories of bravery quickly emerged. Among those celebrated was Samir Zitouni, an LNER employee who was hospitalized after risking his life to save others. Transport Secretary Heidi Alexander praised his “bravery beyond measure,” adding, “There are people who are alive today who wouldn’t be … were it not for his actions.” Zitouni’s family affirmed that he has always been a hero to them.

Myth of Bystander Apathy Challenged

Experts in bystander intervention are increasingly suggesting that the notion of bystander apathy is a misconception. Prof Stephen Reicher from the University of St Andrews argues that people are more likely to act selflessly in moments of crisis. “The notion that people panic and run screaming for the exits is a Hollywood fiction,” he said, citing incidents such as the 7/7 attacks and the 1999 Admiral Duncan pub bombing, where individuals worked together to help one another despite the danger.

Research conducted during the Leytonstone tube attack in 2015 revealed remarkable coordination among bystanders. Some individuals directed others away from danger, while others confronted the attacker. This collective action underscores that heroism often emerges from group dynamics rather than isolated actions.

Prof Clifford Stott, a psychologist at Keele University, supports this view, emphasizing that modern research debunks the myth of bystander apathy. “What modern research shows is that the public are very good at protecting themselves, and the heroic actions that hit the headlines are actually underlying, natural tendencies in all of us,” he explained. He advocates for cultivating this potential, particularly as society faces increasing challenges, including climate-related emergencies.

Empowering Communities to Act

Prof John Drury, a social psychologist at the University of Sussex, emphasizes the importance of authorities supporting community action during emergencies. He suggests that the language used by first responders is critical in fostering a collective spirit. “Talk about ‘the community’ rather than ‘the public,’ and about ‘us’ and ‘we’,” Drury advised. This approach can enhance the sense of connection among individuals, encouraging them to band together in times of crisis.

Dr Gill Harrop, who leads the Bystander Intervention Programme at the University of Worcester, noted that many institutions are actively working to build a culture of helping. “We’re seeing this happening now with bystander intervention training in schools, colleges, universities, policing, and even the NHS,” she said. “We are slowly but surely creating communities of active bystanders. And that’s wonderful.”

The research and experiences shared by these experts indicate a significant shift in understanding human behavior during crises. Rather than viewing individuals as passive observers, there is a growing recognition of the innate heroism that can surface when people come together to support one another. This perspective not only reshapes how society views emergencies but also highlights the need for structures that empower individuals to take action, ultimately fostering a more resilient community.