Engineers at Purdue University have made significant strides in designing the first reusable lunar landing pad, as detailed in a recent paper published in Acta Astronautica. Led by Shirley Dyke, the team emphasizes the necessity of utilizing local lunar regolith materials to construct durable structures on the Moon, given the prohibitive costs of transporting materials from Earth.

Understanding the local materials is critical for building lasting structures. While ancient builders, such as those who constructed the Great Pyramids, relied on the known properties of limestone, lunar engineers face a unique challenge. They currently lack comprehensive data on the mechanical properties of lunar regolith, which is essential for creating a safe and effective landing pad for heavy rockets engaged in resupply operations.

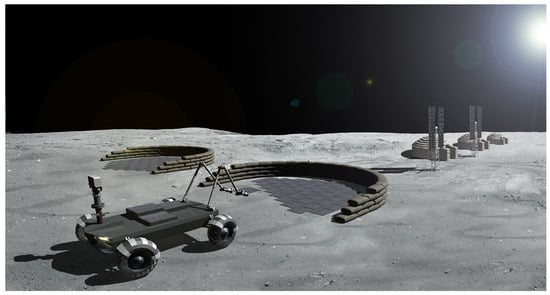

One might question the need for a dedicated landing pad, as rockets like SpaceX’s Starship could theoretically land on any flat surface. Nevertheless, the intense thrust from rocket engines can kick up dust and debris, posing risks to nearby structures and the rocket itself. As such, mission planners advocate for the establishment of a structured landing pad, akin to those used on Earth, to mitigate these hazards.

Current knowledge indicates that constructing a landing pad on the Moon necessitates using lunar regolith due to the high expense of transporting concrete from Earth. Dr. Dyke notes the lack of understanding regarding the strength and behavior of sintered regolith—an essential factor in developing a reliable landing pad. While simulants exist to mimic lunar regolith, they do not fully replicate the unique conditions of the Moon.

When designing a landing pad, engineers must consider both its mechanical and thermal properties. The team has made preliminary estimates of structural characteristics based on existing literature, hypothesizing that sintered regolith may exhibit brittleness and weaker tensile strength compared to compressive strength. The material is also expected to be thermally insulative, which could lead to cracking from repeated rocket launches.

Temperature variations on the lunar surface, driven by the 28-day lunar day/night cycle, add another layer of complexity to the design. The pad will undergo significant expansion and contraction, creating potential warping stresses that could lead to structural failure. To address these challenges, the researchers propose a pad thickness of approximately 0.33 meters (or 14 inches), which balances the need for durability against the risks of thermal stresses.

Despite the careful planning, failure modes remain a concern. Frequent rocket landings could lead to spalling, where pieces of the pad chip off due to thermal expansion and contraction. While the structure can be designed to maintain its integrity, repeated stresses may ultimately compromise its ability to support future landings.

To validate the landing pad design, the authors recommend conducting in-situ testing on the Moon. Upcoming lunar missions are expected to gather more data on regolith properties and test the pad’s performance under unique lunar conditions. This approach will allow engineers to refine their designs over time.

Dr. Dyke envisions that robotic systems will play a crucial role in constructing and maintaining the landing pad. The challenges of human operation in bulky space suits make robotics an essential component in this endeavor. As NASA and other space agencies work towards returning astronauts to the Moon, engineers hope to enhance their understanding of lunar materials to inform the construction of a safe and effective landing pad.

The iterative process outlined in the paper could eventually yield a functional entry point to our nearest celestial neighbor, paving the way for sustained lunar exploration.