The integration of advanced technology in manufacturing, including smart CNC controls and industrial robots, has transformed production processes. However, despite these innovations, the importance of tool geometry remains paramount. The effectiveness of cutting operations is ultimately determined by the precise interaction between the cutting tool and the material, underscoring the need for careful selection of tool characteristics.

Smart Technology Meets Fundamental Physics

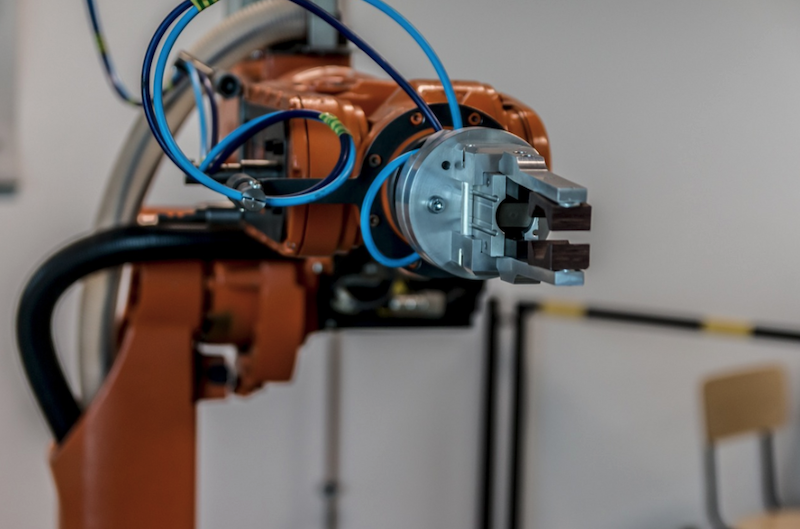

Modern manufacturing now relies heavily on robots to load parts, while CNC controls adjust feeds and speeds in real time. Despite the sophistication of these systems, the fundamental physics of chip formation has not changed. Factors such as helix angles, rake angles, and flute counts continue to play a critical role in determining cutting forces, heat generation, and overall surface finish. If these parameters are not optimized, even the most advanced systems struggle to maintain efficient operations. The selection of the correct end mill is crucial, especially for maintaining productivity in unattended robotic cells.

Research initiatives, such as those conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), demonstrate the importance of these fundamentals. Their studies incorporate digital twins and real-time monitoring to analyze how AI and sensors adapt machining conditions. However, the success of such advanced setups heavily relies on having appropriate cutting tools in place. AI-enhanced analytics can improve already robust processes but cannot compensate for poor geometry.

The Impact of Tool Geometry on Production

In high-mix job shops, where automation is commonplace, the choice of tool geometry has significant implications for production efficiency. A typical scenario might involve machining stainless steel brackets in the morning and aluminum housings in the afternoon. While CNC parameters may change seamlessly through programming, the actual performance is dictated by the geometry of the tools used.

Studies indicate that even minor adjustments in tool geometry, such as edge radius and rake angle, can substantially affect cutting forces and surface quality. A recent investigation revealed that optimizing tool micro-geometry not only reduced cutting forces but also improved surface roughness, contributing to enhanced consistency and tool longevity across various machining tasks.

For instance, a nominally similar 10 mm carbide end mill can exhibit vastly different behaviors depending on its design, such as helix angle or flute count. A polished, high-helix, 3-flute cutter may perform more effectively in aluminum applications compared to a standard 4-flute tool, which might lead to operational issues like chip packing if not selected correctly.

As production environments shift to robotic operations, maintaining process robustness becomes increasingly pivotal. Unlike human operators, robots do not have the capacity to adjust their actions based on auditory cues; they continue loading parts unless the process is fundamentally flawed. Tool geometry serves as the first line of defense against such failures. For example, when machining hard stainless steel, a small corner radius can alleviate stress at the tool tip, thereby mitigating the risk of chipping and maintaining dimensional stability throughout the production run.

In addition, flute count plays a vital role in chip evacuation, especially in intricate pocket machining. A design featuring two or three flutes with adequate chip space enables efficient high-feed strategies, while a four-flute tool may inadvertently result in heat buildup and chatter, ultimately affecting overall performance.

Integrating Geometry into Smart Manufacturing

For manufacturers already investing in smarter CNC systems and robotics, it is essential to formalize tool geometry decisions. One effective strategy is to standardize “tool families” based on material and operation, rather than merely diameter. For instance, for aluminum machining, specifying high-helix, polished 3-flute tools with a small corner radius for roughing and finishing can lead to improved outcomes. In contrast, for hard steel applications, low-helix, multi-flute designs with specific edge preparations may be more appropriate.

When new components are introduced to a robotic cell, it is crucial to not only evaluate feeds and speeds but also scrutinize helix angles, flute counts, and corner geometries for all primary cutters. Simple questions can guide this evaluation: Is the flute configuration capable of clearing chips effectively? Is the corner design robust enough for the intended engagement? Does the edge preparation align with the material and coolant strategy?

Furthermore, manufacturers should create a feedback loop that integrates lessons learned from tool geometry performance into their standards. When specific geometries consistently yield superior surface finishes or fewer operational alarms, these should become standard practices rather than viewed as isolated successes. Over time, this approach will cultivate a library of geometries that support effective automated behaviors.

In conclusion, while smart CNC controls and industrial robots enhance manufacturing capabilities, they can only optimize the processes that are established. Tool geometry remains a fundamental element that defines the cutting operations being optimized. By prioritizing geometry as a critical design consideration rather than an afterthought, manufacturers can maximize the benefits of every sensor, robot, and algorithm implemented on the shop floor.