Connecticut universities are grappling with significant losses in federal funding for research, amounting to tens of millions of dollars. This situation has forced researchers to seek alternative funding sources to continue their critical work. One notable example is Amy Bei, a professor of epidemiology at Yale University, who is striving to advance her malaria research despite setbacks.

On May 1, Bei received a cancellation notice from the federal government regarding a $300,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This funding was intended for the initial phase of a project aimed at tracking the spread of malaria within communities. Previously, in January, she had also received a stop-work order for a separate project in Chad, where she was assisting local laboratories in enhancing genomic surveillance capabilities. The funding for this project came from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

The cancellations and funding pauses have impacted not only Bei’s work but also many other researchers at Yale and other institutions in Connecticut. Lindsay DiStefano, the interim vice president for research at the University of Connecticut, reported that the university had lost approximately $41 million due to grant cancellations and nonrenewals by mid-October. To mitigate the impact, the university allocated about $1.6 million of its own funds to support certain projects.

At Yale, Michael Crair, vice provost for research, indicated that as of August 12, the university had seen the cancellation of 50 grants, with an additional 22 either partially cancelled or paused. Crair described the total financial impact as “tens of millions of dollars,” emphasizing that these cuts jeopardize vital research that contributes to medical breakthroughs, humanitarian efforts, and technological advancements.

Real-World Implications of Research Cuts

Since the early 2000s, Bei has dedicated her research efforts to understanding the complexities of malaria, having begun her work in Tanzania to study drug resistance and potential vaccine candidates. She explained that malaria is not merely a laboratory issue; it poses a severe public health challenge with profound effects on communities.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reported approximately 1.2 million malaria cases and 200 deaths in Senegal in 2023. The parasite’s ability to adapt complicates efforts to develop effective vaccines and treatments. Bei noted that while much progress has been made in combating malaria, the parasite’s evolving nature poses ongoing challenges.

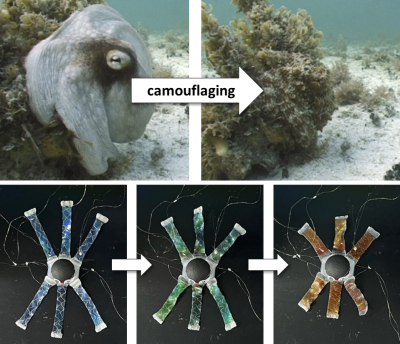

Researchers are exploring biomarkers originating from mosquito saliva to assess the effectiveness of malaria prevention strategies, such as distributing insecticide-treated mosquito nets. These markers are particularly valuable in areas where asymptomatic transmission may occur, allowing the disease to persist under the radar despite a lack of evident symptoms in the population.

Seeking Alternative Funding for Continued Research

In light of the funding losses, Bei has sought alternative sources to sustain her research. She has secured support from the philanthropic arm of Tito’s Handmade Vodka to continue certain aspects of her NIH-funded work. This funding, along with internal grants from Yale, has enabled her team to maintain the USAID project in Chad, which focuses on training local researchers in genomic surveillance techniques.

Despite these efforts, the disruptions caused by the funding cuts remain significant. Natasha Turyasingura, a Ph.D. student from Uganda involved in the Chad project, faced delays in her planned trip to train local researchers on a new DNA sequencing panel due to the U.S. government’s order to halt the project. As funding has now been secured, she and her colleagues plan to travel to Chad in December.

The new U.S. administration’s policies have also personally affected Turyasingura, as her visa duration was reduced from one year to three months, complicating her ability to conduct research abroad. Additionally, community engagement efforts aimed at educating local populations about vaccination benefits have been severely limited due to the halted funding.

Bei continues to receive limited NIH funding for developing a next-generation malaria vaccine. While the WHO has approved two vaccines, they exhibit low efficacy rates—between 45% and 51% for the 2021 vaccine, and between 66% and 75% for the 2023 vaccine. This protection diminishes over time, highlighting the need for further research.

Collaborating with researchers like Laty Gaye Thiam from the Institut Pasteur de Dakar in Senegal, Bei aims to enhance existing vaccines by targeting different stages of the malaria parasite’s lifecycle. This research seeks to identify the antibodies produced by individuals who are immune to malaria, with the goal of understanding the factors contributing to their immunity.

As Bei and her team explore these avenues, they plan to integrate their biomarker research with the findings from Thiam and others to develop a comprehensive approach to malaria prevention.

The challenges faced by Bei and her colleagues underscore the pressing need for sustained investment in malaria research, which not only impacts affected communities but also holds implications for global health advancements. The ongoing efforts of researchers in Connecticut demonstrate resilience and innovation in the face of funding adversity, as they strive to combat a disease that continues to inflict a heavy toll on populations worldwide.